Our Heritage Timeline

The Mills of Blairgowrie and Rattray

Photo courtesy of Our Heritage Archive

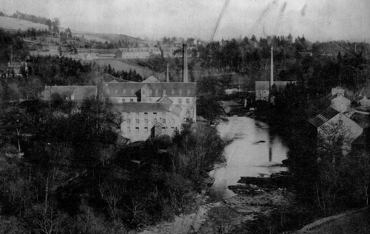

The Mills of Blairgowrie and Rattray

Industrial Powerhouse that was the River Ericht

The River Ericht once drove a remarkable series of 14 spinning mills. Originally working with flax before later changing to spin jute, these mills brought employment and prosperity to the Blairgowrie and Rattray area for much of the last 200 years.

A walk along the leafy riverbanks of the Ericht provides a fascinating glimpse of the once vibrant early industrial landscape in Blairgowrie and Rattray.

The River Ericht falls through 80m between Bridge of Cally and Blairgowrie, and this drop provided the energy to power machinery. This power was harnessed by building weirs, or croys, on the river to divert the water into lades, which channeled it to water wheels, turning them.

Around the Brig O’ Blair there was a cluster of mills, including Corn Mill and Granary, Plash Mill, Meikle (Muckle) Mill and Ericht Linen Works. This group of mills has now been demolished, although some remnants of the wall of the Granary and the Meikle Mill can still be seen in the play park area and the riverside car park area respectively.

The Meikle Mill on the Blairgowrie side of the river existed from 1798 to 1902 and was eventually demolished in 1970.

The Ericht Linen Works was driven by steam and actually only spun jute in its raw form – which had been softened at the Meikle Mill – weaving and calendering it through a machine to give it a smooth surface ready for the Dundee market. First built in 1867, it employed 350 people on 120 power looms. It closed in 1902 and was demolished in 2005 but remnants of original external walls have been incorporated into the building of town houses and flats on the site.

Oakbank Mill, meanwhile, was built by James Grimond, the brother of David Grimond who built the Lornty Mill and was one of the founders of the linen trade in Blairgowrie, in 1830.

In 1832, jute was introduced and James was the first man in Scotland to spin it successfully on a machine – paving the way for the huge Dundee jute industry.

The mill burned down in 1872 but was rebuilt and the Grimond family lived in nearby Oakbank House. Oakbank Mill was also known for its unusual vertical drive shaft from the water wheel and ceased working in 1930. There were a number of terraces of workers cottages along Oakbank Road.

The original Keathbank Mill was built in the 1820s, a little further upstream from its successor which opened in 1864, trebling capacity from 660 to 2000 spindles. The new mill had two main sources of power – a large water wheel and a horizontal steam engine built by Carmichael of Dundee. In 1880, 100 people were employed at Keathbank, which produced flax yarns for the Forfar trade.

The Proctor family owned the mill for a number of years from 1888 to 1932 and they introduced jute. It was acquired by Thomas Thomson Ltd., which produced a fine jute thread by water power alone.

In 1945 rayon was introduced and, in 1979, the mill finally closed before being converted into flats in 2007.

Further up the river were Ashbank Mill and Bramblebank Mill on the Rattray side. Ashbank Mill was built in 1836 by John Baxter for spinning flax imported into Dundee from the Baltic ports. It was destroyed by fire in 1918 and never rebuilt.

Fire was a serious hazard in spinning mills due to the combination of dust from fibres, oil and wooden construction.

The next mill further upstream, Westfield Works on the Rattray side of the river, was also destroyed by fire, this time in 1937. Built in 1836 on the site of the former lint mill owned by Mr Dollas and known as “The Dolly,” Westfield was once one of the largest mills in the district producing jute, flax and tow. It suffered from frequent fires and was eventually converted into a power station for the Bramblebank works by Thomas Thomson Ltd.

In 1963, the Westfield dam was swept away.

Bramblebank Mill, also on the Rattray side of the Ericht, was built in 1833 by David Rattray and shared a weir with Ashbank Mill on the opposite side of the river. It was bought by Thomas Thomson Ltd. in the late 1940s and worked flax before closing down in 1963. Bramblebank was partly destroyed by a fire in 2021.

Brooklinn Mill on the Blairgowrie side of the river was built in 1843 by David Grimond, son of the founder of Lornty Mill and nephew of James. Brooklinn was driven by water from Lornty Burn, which was dammed in two places across the deep ravine. However, there were problems with water supply after the dams burst before a concrete dam was built in the 1960s.

The mill then spun rayon yarn for the pile of tufted carpets before cheap imports undermined production and the mill closed in 1979. It was subsequently converted into a private residence in the mid 1980s, with the smaller building, the old warehouse, now offering holiday accommodation.

The smallest of the mills was Lornty Mill which stands on the Lornty Burn and was built in 1814. The site was originally a lint mill in the 1700s before becoming a snuff mill.

The lade for the mill was only four feet wide and powered four spinning frames. By contrast, Ashgrove Mill which was built in 1866 by John Baxter, who also built Ashbank Mill, had a deep lade with the most powerful water wheel on the Ericht.

Thomas Thomson bought Ashgrove in 1934 to produce flax and jute, and although a large fire in 1953 destroyed the main building, it was rebuilt and operated until closing in 1979.

Eastmill was built in the 1720s and was initially a lint mill. It was later the first mill on the river to close down in 1876 and nothing now remains.

Westmill was built on a site which was formerly a bleaching field and relied on a good water supply for power. It burned down just after the First World War and was a ruin for many years.

The most northerly of all the mills in the district was Craigmill on the Rattray side of the Ericht. It was built by George Saunders just below Craighall Bridge and was driven entirely by water power. The Misses Rattray of Craighall built a school there for the children of the mill workers.

This article was written by Clare Damodaran and was published in the Blairgowrie Advertiser on 27th October 2020 as the first of two parts entitled “Down Memory Lane.”

PART TWO published 3rd November 2020

Workers flocked from far and wide for the mill town boom. Blairgowrie population soared to over 7000.

Flax is amongst the oldest crops in the world. It has been grown since the beginnings of civilisation, primarily for its use in linens though the seed linseed is also a source of oil.

Burial chambers in Egypt, dated back to about 3000BC, depict flax cultivation and clothing made from flax fibres. The plant grows well in Scotland and linen has been produced locally for many centuries. The processing of flax involves stripping off the seeds and then soaking the plants in water for a couple of weeks to soften the outer layers of the stalk.

‘Retting ponds’ where this process was carried out, are common in the Scottish countryside. The flax was then beaten with wooden knives to separate the unwanted bark from the long fibres, which is known as scutching, and then combed through a set of iron spikes to split and straighten the fibres, a process known as heckling.

These processes were originally carried out by hand as was the subsequent spinning of the flax fibres into thread and then weaving this into linen cloth.

By the middle of the 18th century mechanical scutching machines driven by water power were developed and a large number of new Scottish lint mills were built. This was followed , in the latter half of the century, by the development of spinning machines.

Blairgowrie and Rattray, with their considerable water power, were obvious sites for building spinning mills that used the new technology.

The mills of Blairgowrie were built by a series of entrepreneurs eager to take advantage of the business opportunities offered by the mechanisation of the textile industry.

The earliest known spinning machinery was installed in a lint mill in Rattray in about 1796 and this later grew into the Erichtside Works. This was followed by the construction of a new purpose-built mill in Blairgowrie, the Meikle Mill, just above the Brig O’ Blair in 1798.

Mill construction in the town after this was infrequent until about 1830 by which time a new generation of more sophisticated and reliable spinning machinery had become available.

Some seven new mills were then built between 1830 and 1845. However, as the power from the river was limited and not really sufficient to drive heavy power looms, the Ericht mills concentrated on spinning thread, and machine weaving was carried out in the large Dundee mills which were powered by steam engines.

Not enough flax was grown in Scotland to satisfy the demand from the Scottish spinning mills and most fibre was imported, much of it from Russia where production costs were low.

Competition arose, however, when the East India Company started to import a somewhat similar but rather cheaper fibre – jute – from India.

It was not until 1832 that the problems of spinning this more brittle fibre on conventional spinning machines were overcome by softening it first in whale oil. From then, most of the Blairgowrie and Dundee linen mills progressively switched over to spinning the new material.

The linen industry in north-east Scotland had traditionally produced coarse linen cloth and adapted easily to the production of coarse jute fabrics.

The jute industry began to decline at the start of the 20th century, mainly due to competition from mills in India where production costs were much lower.

The Ericht mills became progressively more uneconomic and started to close. Despite minor booms during the two world wars and experiments such as spinning artificial fibres, the last working mills on the Ericht were forced to shut down in 1979.

Between the years 1801 and 1881 the combined population of Blairgowrie and Rattray rose from less than 1000 to over 7000. This was directly attributable to the growth of the spinning industry, which, at its peak, employed about 2500 people.

Unskilled workers came from many places including Ireland where they were escaping the famine, the Highlands, where they were victims of the clearances, and from the slums of Glasgow and Dundee.

Skilled workers were highly prized and many had travelled widely between different textile manufacturing centres in the UK and on the Continent.

Working conditions were harsh by today’s standards, especially in the early 19th century. The working week consisted of six days, from 5.30am to 7pm, with an hour off for breakfast and another for lunch.The factory floors could be cluttered and hot with dust and oil fumes which led to the spread of respiratory diseases such as bronchitis. The machinery was also very noisy and many workers went deaf. Quite young children were employed, working similar hours to their parents. Conditions improved slowly over the years, but even during the First World War, the working week was still five and a half days-a-week and 10 hour days starting at 6am.

By this time, however, laws had been passed requiring working children to spend a certain proportion of their week attending school. Many of the workers lived in houses or hostels belonging to and sited close to the mills, a few of which still remain.

To learn more visit www.blairathistory.org

www.cateranecomuseum.co.uk – A Spin Along the Ericht

www.canmore.org.uk/site/112172/blairgowrie-oakbank-mill

https://www.verdantworks.co.uk/

Read ‘A Social History of Blairgowrie and Rattray’ by Margaret Laing

‘ The Mills of the Ericht’ by Peter Dawson and Margaret Laing

Previous Page